In physics, few concepts are as widely used in daily life as work. Whether you push a shopping cart, lift a bucket, or pedal a bicycle, you are performing work in the scientific sense. But what exactly counts as work? How do we measure it? And why does the work done formula play such an important role in understanding energy, machines, and motion?

This article explains the idea of work in simple terms, explores the formulas used to calculate it, and highlights real-life examples where the concept becomes useful.

What Is Work in Physics?

In everyday language, “work” means putting in effort. In physics, however, effort alone does not qualify as work. Scientific work is done only when a force causes displacement. If you push a wall with full strength but the wall doesn’t move, no work is done, no matter how tired you feel.

So, in physics:

-

Work happens when a force acts on an object

-

The object must move because of that force

This definition helps us measure how much energy is transferred from one object to another.

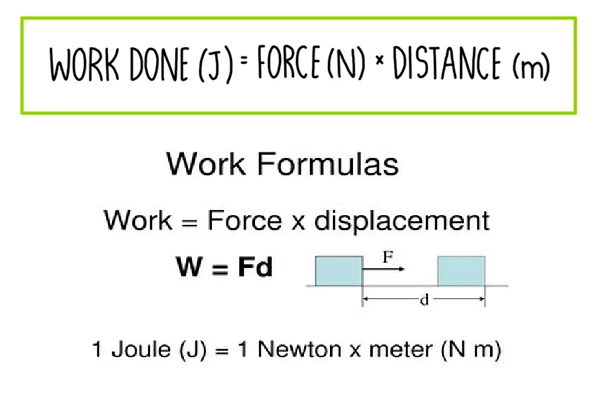

The Basic Work Done Formula

The simplest and most commonly used formula for work is:

Work = Force × Displacement × cos(θ)

or

W = F × d × cos(θ)

Here’s what each term means:

-

W = Work done (Joules)

-

F = Applied force (Newtons)

-

d = Displacement caused by the force (meters)

-

θ = Angle between the direction of force and displacement

This formula shows that work depends not only on the strength of the force but also on the direction in which it acts.

Why Does the Angle Matter?

The angle θ tells us how much of the applied force actually contributes to moving the object.

-

If θ = 0° (force and motion in the same direction),

cos(0°) = 1, so W = F × d.

This is the case when you push a box straight ahead. -

If θ = 90° (force is perpendicular to motion),

cos(90°) = 0, so W = 0.

For example, if you carry a bag while walking, the upward force of your hand does no work on the bag in the forward direction. -

If θ > 90°, work becomes negative, meaning the force opposes displacement.

Friction is a common example—it always does negative work because it resists motion.

This angle-based explanation helps us analyze complex movements and forces acting in different directions.

Work Done Formula in Special Cases

1. Work Done Against Gravity

When you lift an object vertically, you work against the force of gravity.

Work = Weight × Height

where weight = mg (mass × gravitational acceleration)

So,

W = m × g × h

Example: Lifting a 10 kg bucket to a height of 2 meters

W = 10 × 9.8 × 2 = 196 Joules

2. Work Done by a Variable Force

Sometimes the force changes with distance—for example, stretching a spring. For such cases, work is calculated using calculus:

W = ∫ F(x) dx

For a spring following Hooke’s law:

W = ½ k x²

where k is the spring constant and x is the extension.

3. Work Done When Force and Displacement Are Opposite

When a force works against motion (like friction), work is negative:

W = –F × d

Negative work reduces the object’s energy instead of increasing it.

Units of Work

Work is measured in Joules (J).

One Joule is the work done when a force of one Newton moves an object by one meter.

In some fields, work may also be expressed in:

-

Kilojoule (kJ)

-

Calorie (used in food science)

-

Kilowatt-hour (kWh) (used in electricity billing)

Understanding the Relationship Between Work and Energy

Work and energy are closely linked. When you do work on an object, you transfer energy to it. This is why energy is also measured in Joules.

Examples:

-

When you push a car, you transfer kinetic energy to help it move.

-

When you lift a bag, you give it gravitational potential energy.

-

When a machine does work, it converts electrical or mechanical energy into useful motion.

Real-Life Applications of the Work Done Formula

1. Lifting Objects

Construction workers calculate the work needed to lift materials to certain heights so they can choose proper machinery.

2. Sports

Athletes unknowingly use this concept—lifting weights, running uphill, or throwing a javelin all require work based on force and displacement.

3. Engineers and Machines

Engineers design engines and motors by evaluating how much work they must perform to move a load.

4. Electricity Bills

When you see “kilowatt-hours” on your electricity bill, it is actually a measure of the work done by electrical appliances over time.

Common Mistakes Students Make

-

Confusing effort with work

-

Ignoring the angle between force and displacement

-

Forgetting that no displacement means no work

-

Mixing up mass and weight

-

Using the wrong units

Understanding these mistakes helps build clarity and a stronger grasp of physics fundamentals.

Conclusion

The work done formula is a core concept in physics that helps explain how forces move objects and how energy is transferred. Whether you are a student, an engineer, or simply curious about how the physical world functions, knowing this formula gives you a deeper understanding of everyday activities. From lifting groceries to powering machines, the idea of work is everywhere—and mastering it opens the door to exploring more complex ideas in mechanics and energy.